In the Septuagint (LLX), Judith is a bad-ass heroine, heartily accepted and lauded by her people after she saves them from Holofernes. She is portrayed as quite independent – relying upon her faith in God, but very inner directed, brave, and splendid. Lots of intertextual links to Jewish heroes, male and female. Jerome’s Latin Vulgate (4th C CE) turns her into a chaste super pious widow who is basically following God’s direction – still a heroine, story much the same, but more directed – not so much agency – and not so fully respected. A story you would expect from a celibate Christian priest.

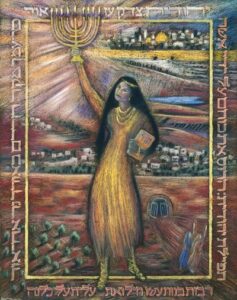

There is zero in Jewish tradition concerning Judith until about 1000 CE. Never was a Hebrew version of the LLX story. Jerome, in making the Latin Vulgate claims to have translated from Hebrew but this cannot be established. None of the Jewish historians, philosophers or rabbis mention her until she appears in the middle ages. Her story then is similar to LLX, but gets wrapped into multiple midrashic and liturgical stories of Hanukkah and Judah. She becomes quite prominent as a Jewish heroine (see first illustration – above), perhaps partly because it is a time of increasing nationalism (12th-14th centuries or so), perhaps in reaction to Christian adoration of the Virgin Mary. Judith remains a hero to the Jewish people over time (see second illustration).

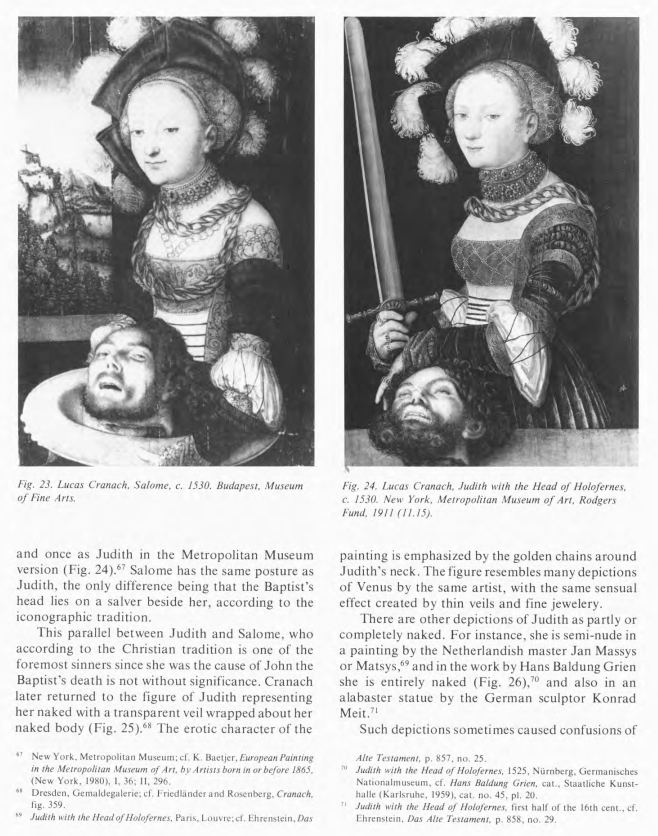

Christian art in the 15th century mixed Judith up with quite misogynist views of women. The art in last frame shows that she was conflated with Salome and both were portrayed as rather vile seducers.