Thank you for registering for the Ruach HaYam Shabbaton. We look forward to spending the retreat with you. Please visit our webpage for more information about Ruach HaYam

— Penina Weinberg, Retreat Director and founder of Ruach HaYam.

Thank you for registering for the Ruach HaYam Shabbaton. We look forward to spending the retreat with you. Please visit our webpage for more information about Ruach HaYam

— Penina Weinberg, Retreat Director and founder of Ruach HaYam.

I visited the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston to see the painting Elijah in the Desert by Washington Allston. http://www.mfa.org/collections/object/elijah-in-the-desert-30844

A great deal of my time is spent viewing digital photos and images. In fact, I found the image of this painting through a google image search for Elijah. As a small jpg, the picture is stunning enough – a stark portrayal it seems, of Elijah in the throes of despair. I used this image as a banner for a study session I’m leading called “Elijah the Prophet: Zealotry, Despair, and Hearing kol d’mama daka.” By great coincidence, the original hangs in the MFA. In fact, it was the first ever acquisition for the MFA. In 1870, Allston was such a highly regarded American painter that the donor of the painting suggested naming the museum after Allston. I did not know this prior to seeing the painting. I just thought it would be a good idea to see the original.

A great deal of my time is spent viewing digital photos and images. In fact, I found the image of this painting through a google image search for Elijah. As a small jpg, the picture is stunning enough – a stark portrayal it seems, of Elijah in the throes of despair. I used this image as a banner for a study session I’m leading called “Elijah the Prophet: Zealotry, Despair, and Hearing kol d’mama daka.” By great coincidence, the original hangs in the MFA. In fact, it was the first ever acquisition for the MFA. In 1870, Allston was such a highly regarded American painter that the donor of the painting suggested naming the museum after Allston. I did not know this prior to seeing the painting. I just thought it would be a good idea to see the original.

It’s so easy (for me at least) to forget how powerful a painting is in the original. I sat in front of Elijah for maybe an hour, looking from all angles, up close, far away, to the right and to the left, sitting, standing, letting thoughts and feelings run through me. People passed through the gallery, mostly cruising past the room full of paintings, only infrequently stopping for more than a couple of minutes for anything. So the first observation was: how easy it is for humans to walk without taking in impressions, without feeding on the painter’s laborious and careful work. Similar to speed reading through novels, without enjoying the precise language crafted by the writer.

It was a treat for me to have the time to sit and absorb this one painting, and to have knowledge of the text behind it (1 Kgs 19) (17:1–7 according to MFA). Here is what I saw. The sunlight breaking through over the mountains is striking and brilliant. It appears to highlight Mt Horeb (Sinai) in the distance. It breaks through the clouds of despair. It lands brightly on Elijah’s head as if to convey a message to him (from the divine) that all is not lost. The raven, too, carrying food to Elijah, into the light, may be a beacon of hope and comfort. Yet it’s not clear in the painting if Elijah can see the raven, or the light, any more than it’s clear in the text if Elijah can hear kol d’mama daka, that strange, stringent, quiet, ice-breaking voice of God. The painting illuminates the central question of the text: is Elijah grateful and learning, or is he unable to hear God’s voice? I kept wanting to get my eyes right in front of Elijah’s face, but could not. The painting was tantalizingly out of my reach, as is the meaning of the text.

Ruach HaYam Workshop at Congregation Eitz Chayim, Cambridge, MA

September 15, 2016. Ruach HaYam study sessions provide a queer Jewish look at text, but are open to any learning or faith background and friendly to beginners.

Study starts promptly at 7:15 pm. However we open the doors at 6:45 for schmoozing. Feel free to bring your own veggie snack for the early part. —- A parking consideration is in effect for the three blocks around EC during all regularly scheduled events.

Accessibility information: MBTA accessible, all gender/accessible bathrooms, entry ramp.

This study is led by Penina Weinberg.

We will do a close reading of 1 Kgs 19, Prophet Elijah’s flight to the desert, where he prepares himself to die. In what way are Elijah’s fear of Jezebel, his zealotry for God, and his despair, linked to each other? When God attempts to teach Elijah that the divine is to be found in kol d’mama daka, but not in the wind, not in the earthquake, and not in the fire, does Elijah get the message? Note: biblical scholar Athalya Brenner writes that translations for kol d’mama daka, “as various as the RSV’s ‘still small voice’, ‘roaring thunderous voice’, ‘the sound of utmost silence’ and ‘a thin petrifying sound’ are all equally plausible.” We will be assisted in the study of despair by Elizabeth Sweeny who will present some of her work on Elijah and depression. Thank you, Elizabeth!!! 1 K 18:46 – 19:21 is the haftarah for Num 25:10 – 30:1, (parashat Pinchas). We will compare Elijah’s zealotry to the of Pinchas. How does zealotry manifest? In what ways does the text approve and disapprove?

Penina Weinberg is an independent Hebrew bible scholar whose study and teaching focus on the intersection of power, politics and gender in the Hebrew Bible. She has run workshops for Nehirim and Keshet and has been teaching Hebrew bible for 10 years. She has written in Tikkun, founded the group Ruach HaYam and is president emerita and chair of various committees in her synagogue. Penina is a mother and grandmother.

Ruach HaYam Workshop at Congregation Eitz Chayim, Cambridge, MA

August 18, 2016. Ruach HaYam study sessions provide a queer Jewish look at text, but are open to any learning or faith background and friendly to beginners.

Study starts promptly at 7:15 pm. However we open the doors at 6:45 for schmoozing. Feel free to bring your own veggie snack for the early part. —- A parking consideration is in effect for the three blocks around EC during all regularly scheduled events.

Accessibility information: MBTA accessible, all gender/accessible bathrooms, entry ramp.

This study is led by Penina Weinberg.

The Hannah Narrative, 1 Samuel 1:1-2:10, is recited as the Haftarah every year at Rosh Hashanah. R Nahman of Breslev teaches that “During the Days of Awe it is a good thing when you can weep profusely like a child. Throw aside all your sophistication. Just cry before God; cry for the diseases of the heart, for the pains and sores you feel in your soul. Cry like a child before his father.” (From R Noson’s work, “Liketey Eitzot”). The Talmud presents Hannah as an example to all of how to pray. “R. Hamnuna said: How many most important laws can be learnt from these verses relating to Hannah! Now Hannah, she spoke in her heart: from this we learn that one who prays must direct his heart. Only her lips moved: from this we learn that he who prays must frame the words distinctly with his lips.” (B. Berachot 31a-b)

Through many years of reciting the Hannah Narrative at the High Holy Days, I have generally understood the Hannah Narrative to be an example of how one needs to dig into one’s soul and shout out one’s inner longings. In this class, I want to ask the question, what is our responsibility to really listen? Is there a problem in expecting the Other to dig into their soul and to reach out to Us? In the Hannah Narrative, only Penina really listens from her own empathetic soul.

Penina Weinberg is an independent Hebrew bible scholar whose study and teaching focus on the intersection of power, politics and gender in the Hebrew Bible. She has run workshops for Nehirim and Keshet and has been teaching Hebrew bible for 10 years. She has written in Tikkun, founded the group Ruach HaYam and is president emerita and chair of various committees in her synagogue. Penina is a mother and grandmother.

Ruach HaYam Workshop at Congregation Eitz Chayim, Cambridge, MA

May 26, 2016. Study starts promptly at 7:15 pm. However we open the doors at 6:45 for schmoozing. Feel free to bring your own veggie snack for the early part.

Ruach HaYam study sessions are open to any learning background and friendly to beginners. For those arriving by car, parking is allowed within 2 blocks on event nights.

We are proud to have the co-sponsorship of Keshet for this event!

This study will be co-led by Mischa Haider and Penina Weinberg. They have recently begun collaborating on articles drawing wisdom from ancient Hebrew texts and applying it to understanding and undermining the assault on transgender womanhood today. In this study, we will look closely at the story of Queen Jezebel in 1 and 2 Kings. As a Phoenician princess, she was educated in religion and governance, and well able to sustain 400 prophets and run the kingdom. Yet she was out of place in the Israelite kingdom, scorned for her prowess, feared, and ultimately thrown to the dogs. In seeking to understand the forces which drove the King of Israel to destroy her, we seek to understand two things about the modern assault on transgender womanhood. What are the forces that drive this assault, and how can we honor and foreground the majestic souls of our modern day Queen Jezebels?

Mischa Haider is a transgender activist and mother. She is an applied physicist at Harvard University who studies applications of mathematical and physical models to social networks. She has written in the Advocate and Tikkun, and her research has been published in Applied Physics Letters. She also has a blog on the Huffington Post and is on the Board of Trustees of Lambda Literary.

Penina Weinberg is an independent Hebrew bible scholar whose study and teaching focus on the intersection of power, politics and gender in the Hebrew Bible. She has run workshops for Nehirim and Keshet and has been teaching Hebrew bible for 10 years. She has written in Tikkun, founded the group Ruach HaYam and is president emerita and chair of various committees in her synagogue. Penina is a mother and grandmother.

Read Mischa and Penina’s article here: http://www.tikkun.org/

Accessibility information: MBTA accessible, all gender/accessible bathrooms, entry ramp.

Ruach HaYam Workshop at Congregation Eitz Chayim, Cambridge, MA

May 26, 2016. Study starts promptly at 7:15 pm. However we open the doors at 6:45 for schmoozing. Feel free to bring your own veggie snack for the early part.

We have a treat coming up! Our friend and wonderful teacher, Jonah P will be facilitating our next study. We will learn about Rabbi Yochanan, a recurring character in the Talmud, who is renowned not only for his Torah, but also for his great beauty and his deep love for his hevruta. He’s also famous for being the central character in one of the Talmud’s most homoerotic tales. In this session, we’ll examine this and a few other tales in which Rabbi Yochanan stars, get acquainted with this fascinating figure, and explore how his identity impacts his Torah learning.

This will be a text learning session which is open to any learning background and friendly to beginners (English translations provided for everything).

About the facilitator: Jonah P. has been reveling in the intersection of queer/trans and Judaism since becoming active in the Boston Jewish community in 2011. He recently completed a year of learning at Yeshivat Hadar.

Picture credit: http://

Accessibility information: MBTA accessible, all gender/accessible bathrooms, entry ramp.

Purim is a time when we remember to think about Esther and perhaps learn to think about Vashti. I present here a small picture gallery. Images have the power to convey ideas very quickly.

I hope you will enjoy this visual tour and that this will stimulate thoughts about Esther, Vashti, gender politics, the meaning of Purim, and your own identity.

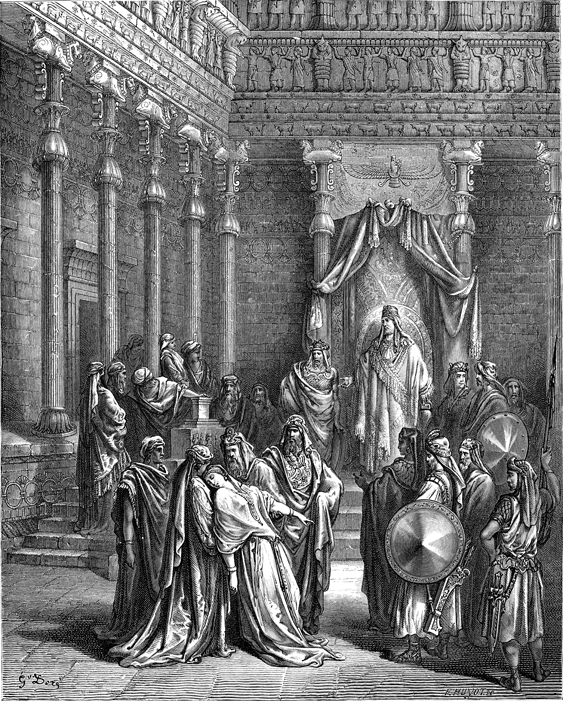

The first image is by Gustav Dore and can be found in digital format in the Pitts Theology Library at Emory University. Notice Vashti’s power, independence and command. She is recognizably a woman, but on her own terms.

Now we have Dore’s Esther, version one. Here we see Esther in similar command, accusing Haman before the King Ahasvuerus. Notice how Esther dominates both King and subject. Like Vashti she is a woman on her own terms.

Dore has another view of Esther. I believe in this case he is illustrating a verse from the Greek version. Note how Esther has lost her power and how King Ahasvuerus dominates. In her aspect as woman she is now subject of male gaze, vulnerable, not in command.

Esther Faints

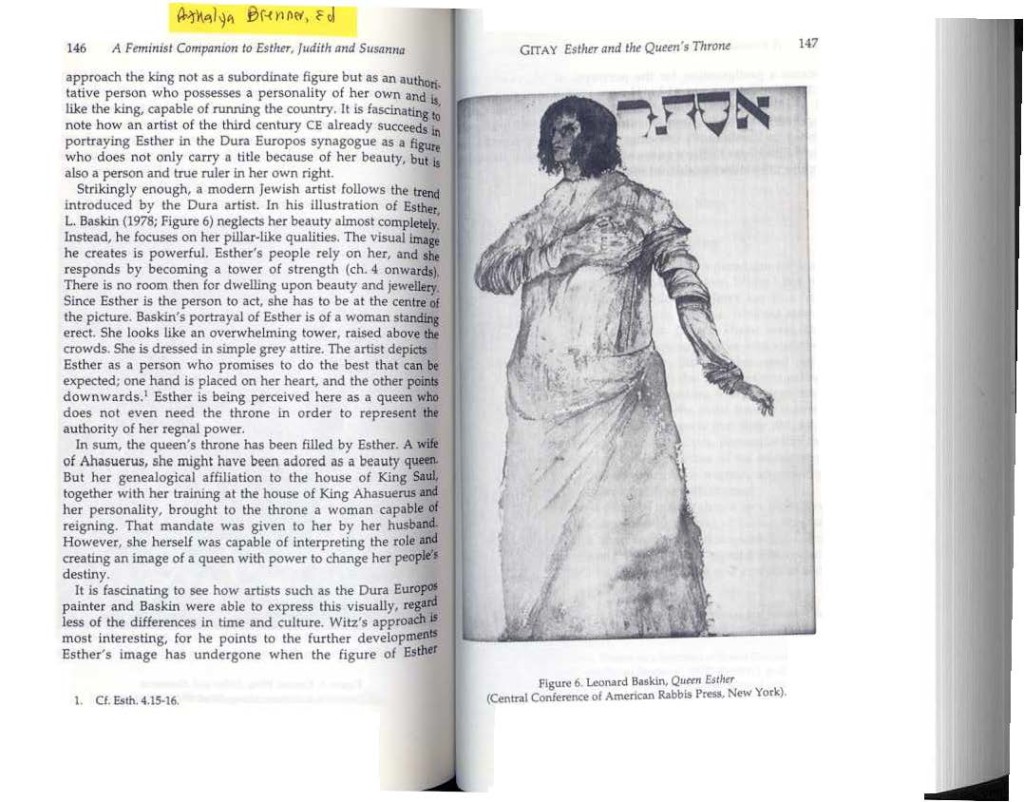

And finally, one more modern illustration from Athalya Brenner’s book, A Feminist Companion to Esther, Judith and Susanna. The illustration is by Leonard Baskin and is discussed on the page. This version of command is strikingly different in quality. Brenner calls it “pillar-like.” It seems to lose characteristics of gender altogether. Even more so, seems to lose characteristics of being human.

Talk about escaping to Canada if one’s preferred candidate does not win the election is plentiful. It has been plentiful before, when George Bush was re-elected, after 9/11 and so on. No doubt escape hatches will be touted again and again. This calls to my mind rabbinic commentary on the story of Elimelech and his wife Naomi. What follows is not a political statement, but a rumination on where the consequences of escape touch upon my personal life.

In the book of Ruth, in the space of the first 5 verses, we learn the following: There was a famine in Bethlehem, in the land of Israel; Elimelech and his wife Naomi leave Bethlehem with their two sons to sojourn in Moab; Elimelech dies; their two sons die without offspring; Naomi survives alone. This is clearly a tragedy. The text tells us how tragic by this: “And the woman was left of her two children and of her husband” (Ruth 1:5). Naomi was so bereft that in losing her husband and her two children, she lost her identity, indeed her very name. She is left like a remnant. “R. Hanina said: She was left as the remnants of the remnants [of the meal offering].” (Ruth Rabbah). I mention this so that we don’t overlook the fact that the real tragedy of this moment is on the shoulders of Naomi, who is embittered and alone.

The rabbis interpret that the deaths were a punishment for Elimelech (and I would add Naomi and the children) for leaving the land of the famine. “Why then was Elimelech punished? Because he struck despair into the hearts of Israel… He was one of the notables of his place and one of the leaders of his generation. But when the famine came he said, ‘Now all Israel will come knocking on my door, each one with his basket [for food].’ He therefore arose and fled from them.” (Ruth Rabbah). Elimelech left behind those suffering from famine, rather than taking responsibility for the people of his country.

As I said, talk of escaping to Canada brings this story to my mind, but whether those who might flee this country (now or in the future) are unsafe in remaining, entitled to a better future, or should be frowned upon for leaving behind those less fortunate, is not for me to judge and is not the point of my re-telling. The story leads me personally to my relationship to my Jewish community, to the shul wherein I daven and take on various leadership roles. Two years into my president emerita status and I feel very much like escaping, if not literally from the campus, internally from all responsibility. There are many things I don’t like about how the organization is run, how volunteers are recruited and nourished, and how visions are created (as in NOT). In fact I have been internally escaping for some time.

The response of the rabbis to Elimelech pulls me up short. Not because I am afraid of punishment as such. But I need to think very carefully about my responsibility to the people in my own small country, the land of my shul. These are folks who have nourished me, and whom I have nourished. According to the teaching in Ruth Rabbah, one does not flee from those whom want might be able to help. Is this a moment to double down on my efforts to work with others to create a better community? Or is the a moment to go sojourn in Moab? Not sure about this yet, but I do know I’m not moving to Canada any time soon.

Parasha Ki Tisa is a Song of both longing and danger. First, the longing. Previous to our parsha, Moses has gone up to the top of Mount Sinai, entering the cloud of God’s presence, to remain with God for 40 days (Ex 24:18). While Moses is up on Mount Sinai encountering the Divine, the children of Israel wait expectantly at the foot of Mount Sinai for Moses to return with God’s prescription for a holy life.

Now the period of time is coming to an end and the people are restless, “for this Moshe, the man who brought us up from the land of Egypt, we do not know what has become of him!” (Ex 32.1 Everett Fox translation). They go to Aaron, brother of Moses, and say to him, “Make us a god who will go before us!” (Ex 32.1 Everett Fox translation). There follows the well-known story of the creation of the golden calf from the gold rings of the people, and of the people eating, drinking, and dancing wildly around their creation.

I would like to read the creation of the golden calf as the story of people who are yearning for God’s presence, and who do the best they can in their circumstances to fill that longing. But there is a problem with this reading, and that is where the danger comes it. Although Moses successfully pleads with God not to destroy the people entirely (Ex. 32:31-34), nevertheless God sends a plague upon the people (Ex. 32:35). Moses himself orders the Levites to assassinate 3,000 of the Israelites. (Ex. 32:26-28). If the people were expressing longing for God, how do we understand a world in which they can be punished for doing so?

We can illuminate the Exodus text by following the ancient rabbinic tradition of reading Torah intertextually with Song of Songs. But fair warning, the Song illuminates the danger as well as the longing.

Exodus shows us that the people bear witness to the awesome and physical presence of God on Mt. Sinai, to thunder, smoke, lightening, and shofar blasts when God reveals God’s commandments (Ex. 19:16-20:18). Aviva Zornberg says “At the moment when God spoke at Sinai, a whole nation lost consciousness and regained it.” (The Murmering Deep, pg 246). She quotes from Shemot Rabbah 29:3, which incidentally provides a good illustration of how the rabbis read Song of Songs with the Torah.

Levi said: Israel asked of God two things – that they should see His glory and hear His voice; and they did see His Glory and hear His voice, for it says, “And you said: Behold, God has shown us His glory and His greatness, and we have heard His voice out of the midst of the fire” (Deut. 5.21). But they had no strength to endure it, for when they came to Sinai and God revealed Himself to them, their souls took wing because He spoke with them, as it says, “My soul left me when he spoke” (Songs 5:6).

Zornberg suggests that the people are destabilized by “the shock of God’s voice.” Their souls have left them. And in this destabilized condition, it appears to them that Moses has left them too. Moses has learned from God that it will be possible (and necessary) for the Israelites to build a sanctuary, so that God may dwell amongst them. Ve-asu li mikdash, Ve-shachanti be-tocham. (Ex. 25.8). But the people do not yet know about a Mikdash where God’s Shekhina שְׁכִינָה can dwell amongst them shachanti שכנתי. Their souls have left them, and Moses has left them. They erect the golden calf.

When Moses descends from Sinai, the the Israelites are dancing around the calf. Joshua tells Moses that he hears the cry of war (kol milchamah). However, Moses hears (Ex 32:18, translation Robert Alter)

Not the sound of crying out in triumph,

and not the sound of crying out in defeat.

A sound of crying out I hear.

Moses hears the people simply crying out, neither triumphant nor defeated. I read this as the people crying out from their souls, for God’s presence. This may remind us of Hannah’s prayer:

I pour my soul out before YHWH וָאֶשְׁפֹּךְ אֶת-נַפְשִׁי, לִפְנֵי יְהוָה. Sam 1:15).

Like R. Levi, we can read Song of Songs with the Torah, but we read a little further in the verse and discover how the singer felt when her soul left her, how she sought but could not find her lover, as the Israelites sought and could not find Moses or God. In Chapter 5, the singer is called to the door by her beloved, but hesitates, and then:

I opened to my beloved; but my beloved had turned away, and was gone. My soul failed me [left me] when he spoke. I sought him, but I could not find him; I called him, but he gave me no answer. (Song 5:6)

As the lover called out, so too the Israelites call out with “the sound of crying out.” They don’t yet know about building a Mikdash, so they gravitate to the one thing which they know about that might bring God’s presence – the golden calf. In this reading, they do not have intent to blaspheme, to worship idols, or to turn against their God. Yet, if they are expressing their longing for God in creating the golden calf, it seems harsh that they must be punished. Is it for lack of faith? It still seems harsh, yet very much like a reflection of the real world.

Listen to the Song in conjunction with the punishment of people at Sinai:

And he [Moses] said unto them: ‘Thus says YHWH, the God of Israel: Put ye every man his sword upon his thigh, and go to and fro from gate to gate throughout the camp, and slay every man his brother, and every man his companion, and every man his neighbor. And the sons of Levi did according to the word of Moses; and there fell of the people that day about three thousand men. (Ex. 32:26-28).

And YHWH smote the people, because they made the calf, which Aaron made (Ex. 32:35).

Immediately after the singer of the Song laments over not finding her lover, the next verse says:

The watchmen that go about the city found me, they smote me, they wounded me; the keepers of the walls took away my mantle from me. (Song 5:7)

Who are these watchmen? It is surely dangerous to walk about the city when the very guardians of public safety are liable to beat the walker. Is the walker in a dream? Is she beaten because she is dreaming? Because she is yearning? Because the search she conducts for her lover does not fit with the societal norms of male pursuing female? The moment when the singer of the Song is beaten by the watchman, and the moment when the children of Israel are punished by God (and by Moses), are awe-full moments. Their hearts were full of longing, and then, wham! There are other, and plentiful, times of joy, of success in finding. But punishments are troubling and remind us that the world, then and now, is not always a safe place in which to be out and to follow one’s heart.

Here is the text of Song 5:2-8 in its entirety.

| אֲנִי יְשֵׁנָה, וְלִבִּי עֵר; קוֹל דּוֹדִי דוֹפֵק, פִּתְחִי-לִי אֲחֹתִי רַעְיָתִי יוֹנָתִי תַמָּתִי–שֶׁרֹּאשִׁי נִמְלָא-טָל, קְוֻצּוֹתַי רְסִיסֵי לָיְלָה. | 2 I sleep, but my heart waketh; Hark! my beloved knocketh: ‘Open to me, my sister, my love, my dove, my undefiled; for my head is filled with dew, my locks with the drops of the night.’ |

| ג פָּשַׁטְתִּי, אֶת-כֻּתָּנְתִּי–אֵיכָכָה, אֶלְבָּשֶׁנָּה; רָחַצְתִּי אֶת-רַגְלַי, אֵיכָכָה אֲטַנְּפֵם. | 3 I have put off my coat; how shall I put it on? I have washed my feet; how shall I defile them? |

| ד דּוֹדִי, שָׁלַח יָדוֹ מִן-הַחֹר, וּמֵעַי, הָמוּ עָלָיו. | 4 My beloved put in his hand by the hole of the door, and my heart was moved for him. |

| ה קַמְתִּי אֲנִי, לִפְתֹּחַ לְדוֹדִי; וְיָדַי נָטְפוּ-מוֹר, וְאֶצְבְּעֹתַי מוֹר עֹבֵר, עַל, כַּפּוֹת הַמַּנְעוּל. | 5 I rose up to open to my beloved; and my hands dropped with myrrh, and my fingers with flowing myrrh, upon the handles of the bar. |

| ו פָּתַחְתִּי אֲנִי לְדוֹדִי, וְדוֹדִי חָמַק עָבָר; נַפְשִׁי, יָצְאָה בְדַבְּרוֹ–בִּקַּשְׁתִּיהוּ וְלֹא מְצָאתִיהוּ, קְרָאתִיו וְלֹא עָנָנִי. | 6 I opened to my beloved; but my beloved had turned away, and was gone. My soul failed me when he spoke. I sought him, but I could not find him; I called him, but he gave me no answer. |

| ז מְצָאֻנִי הַשֹּׁמְרִים הַסֹּבְבִים בָּעִיר, הִכּוּנִי פְצָעוּנִי; נָשְׂאוּ אֶת-רְדִידִי מֵעָלַי, שֹׁמְרֵי הַחֹמוֹת. | 7 The watchmen that go about the city found me, they smote me, they wounded me; the keepers of the walls took away my mantle from me. |

| ח הִשְׁבַּעְתִּי אֶתְכֶם, בְּנוֹת יְרוּשָׁלִָם: אִם-תִּמְצְאוּ, אֶת-דּוֹדִי–מַה-תַּגִּידוּ לוֹ, שֶׁחוֹלַת אַהֲבָה אָנִי. | 8 ‘I adjure you, O daughters of Jerusalem, if ye find my beloved, what will ye tell him? that I am love-sick.’ |